A Mystery Inherited, by Carolyn Wray

My strongest memory of Judy is a day she picked Emily and I up from gymnastics in kindergarten. Emily was more like a sister to me, and her mom made me feel completely trusting and loved. When she walked through the gym door from the parking lot, her long, blonde hair swayed behind her. She was one of those people who the mysterious aura of beauty just hangs around. I remember how Huntington’s Disease symptoms began to present in Judy, but above everything, I remember her warm, comforting energy before all that. I cling to a vague recollection of how it sounded when she said my name.

Emily and I would have gone back to their house that day to play. I loved playdates at their house because I got to see all the kittens. Her cat had had kittens, the kittens had kittens, and all three generations roved freely. They’d play with just about anything—jumping for a piece of yarn and batting at balled-up aluminum foil. I felt deflated and confused when my mom helped Emily’s dad bring the kittens to an animal shelter and neuter the remaining one. Judy’s indifference was a glimmer of warning for a far more complicated problem.

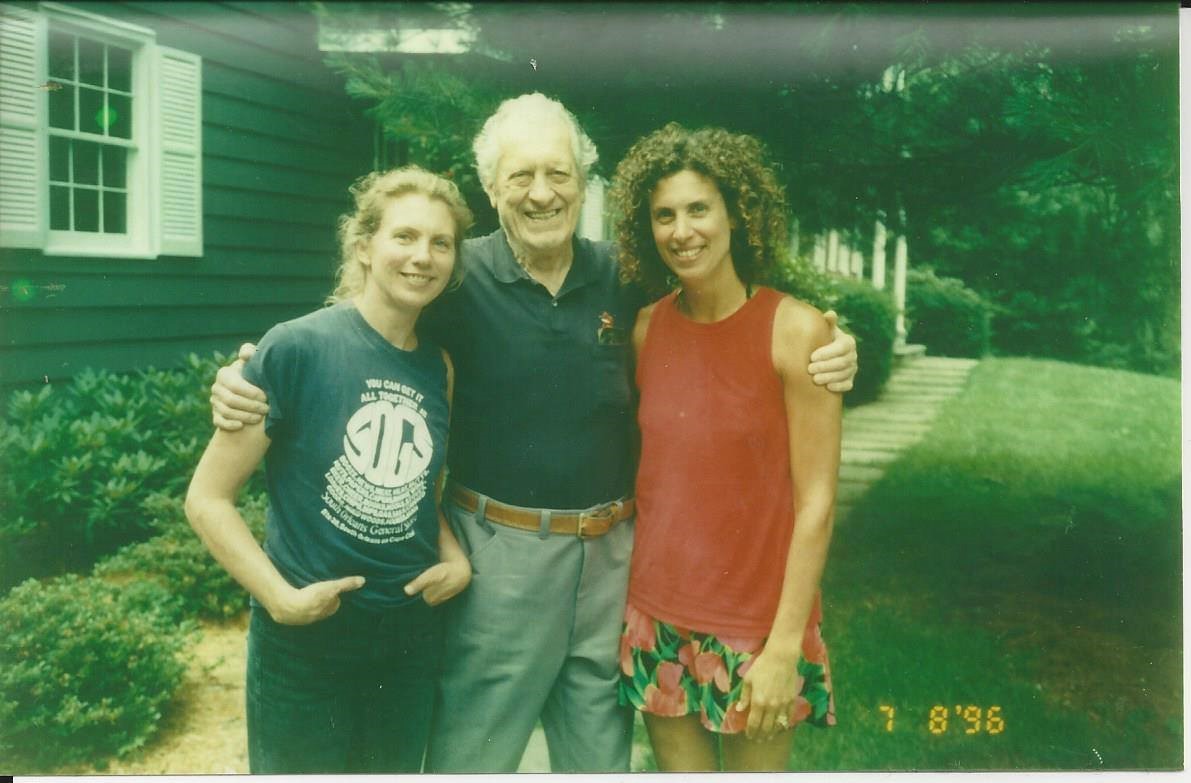

My mom and Judy had known each other since high school, back in my mom’s photography days. She took a black-and-white photograph of Judy on her 35-millimeter film camera. She’s leaning on a fence, cigarette casually hanging between her fingers. She smiles brightly and openly, just the way Emily does. Our moms would drink Diet Coke out of plastic tumblers on our back porch. Over time, it became Emily's dad, Gary, who more often came and sat with my mom. There was a growing tone of gravity.

Judy started moving her mouth oddly at first. With her lips lightly protruding they'd shift towards one cheek and then the other. In the beginning, they would move quickly to the left, right, and then relax. It reminded me of when my little brother would focus on something so hard his tongue would stick out. But Judy started doing it more often and more pronounced, squeezing her lips as far as they would go in every direction on her face.

Oddities like that can seem normal if it’s all you know a person to do, especially if you’re a child. The only movement that struck me as curious was when she started sporadically flinging an arm up into the air. It would go elbow first, shoot straight up, and then drop. It was involuntary, like the movements of the kittens’ tails. I don’t think I commented about it to my parents or anyone. To me, it was still just Judy.

Judy’s adoptive parents had no information on her biological family’s medical history, so the onset of symptoms was entirely mysterious and alarming. It was the nineties, and it took five years to find a doctor who correctly pegged the bizarre affliction as Huntington’s Disease. Still, the progression was like the passing of time, impossible to slow down no matter what they tried. It was devastating to comprehend that going to the right doctor would not bring her back. She continued to slip away, her speech becoming slurry, and Emily got used to dressing herself. We were seven years old when Judy went to a nursing home for good. She had become not only unable to care for herself and her children, but also a danger when left alone.

When my mom shared with me what she knew about Huntington’s Disease back then, she included the fifty-percent chance of inheritance. My heart dropped and panged for my best friend. The only experience I could compare the feeling with was when my favorite doll was mistakenly tossed into the washing machine—I couldn’t pry the door open so just watched her trapped, spinning. But now it was my best friend, nearly identical to me on the outside, who was locked into an unknown fate. As Emily and I grew up together, I kept that knowledge like a secret in my heart, squeezed up tightly as if in a locket, too painful to visit often.

For a long time, the possibility of Emily having HD felt like a faraway problem that we would not have to face for many years. Then we had our thirtieth birthdays, and suddenly a decade doesn’t seem as long anymore. Last month, Emily went forward with testing to find out if she has the gene. I waited with bated breath when she got the results.

She has the gene. Everything stopped. Time stopped. It was like hitting a wall–the wall before and after knowing. Never have I felt more definition in the passing of a moment. It was like a thick bookmark slammed into life.

Emily’s voice was low and factual as she talked me through the details of her results. Her predicted onset is in ten to fifteen years. She volunteered for experimental treatment to build knowledge around the rare disease. She said it'll be worth it to help kids who won't have to grow up losing their mom to Huntington’s like she did.

When I asked how she felt, she said there’d been a pit in her stomach since finding out. Her whole life, she knew the chance was like flipping a coin, but knowing did not make the news easier. Ten years is a long time to live with an awareness of that magnitude, but not nearly as long as the rest of us get to live our lives comfortably. Ten years is also a long time in science, I told her. There’s surely been progress since her mom suffered all those years ago, and there will continue to be advancements.

I don’t know the technical intricacies of HD, but what I know from Judy is that a person's spirit is more resilient that her mind and body. It may become harder to tap into or only seen in an occasional expression, but it is never gone, only dormant. It's still unimaginable to think of Emily sliding into symptoms, but if she does, she’ll never be alone. No matter where it takes her, I’ll visit toting a bag of our favorite things. I will wake up her spirit as often and for as long as I possibly can.

Knowing Emily has been the highlight of my life. It's easy to forget the weight of the situation she's in when she smiles. I still have the half heart from our friendship necklaces we got when we were five years old. We'd run towards each other and fit them together as a greeting. If I have a child, I hope she’s lucky enough to have a best friend like Emily–and I hope I can be the figure that Judy was to me, at her best.